Professor Sian Sullivan, Bath Spa University

PI of Future Pasts

With Mike Hannis (BSU), Angela Impey (SOAS), Chris Low (BSU) and Rick Rohde (Edinburgh)

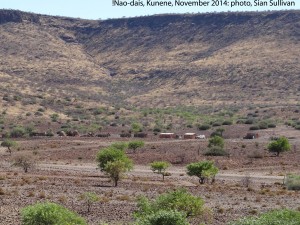

Perhaps inappropriately for a blog on ‘Debating Time’, I am late in submitting a post to introduce Future Pasts. My excuse is that the invitation to contribute a post was sent when I was living in west Namibia, some distance from internet access – at the settlement in this photo.

This is a place called !Nao-dais in Damara/≠Nū Khoen gowab (language), and Otjerate in oshiHerero. The family of Suro, the Damara woman with whom I have worked on and off for twenty years, have herded livestock at !Nao-dais for decades. Currently they are joined by a Himba pastoralist family from Kaokoveld to the north of this area, who inhabit the cluster of huts to the left of this image. These diverse Namibians are also being asked to vacate the(ir) land. A series of affidavits shared with me in October, associated with companies investing in wildlife tourism operations in the area, frames ‘sustainability’ in terms of a landscape aesthetic of ‘pristine, unspoilt wilderness’, marred visually and ecologically by the ‘eyesore’ of local people and their dwellings.

Scratch beneath the surface of one small place, then, and we find very different conceptions of what it means to live well within an environmental context, linked with differing views about what values should be transferred forwards to the future, and about how this might best be enacted. Juxtaposition of these and other cultures of sustainability in the west Namibian context provides the fulcrum around which the Future Pasts project pivots.

The full title of our project is Future Pasts in an Apocalyptic Moment: Green Performativities and Ecocultural Ethics in a Globalised African Landscape. In this introductory blog I will introduce our project and intentions by explaining the key terms of our title, beginning with the last term, which locates our project geographically.

A globalised African landscape

We are working in west Namibia, where three members of our team – myself, Rick Rohde and Chris Low – have conducted ethnographic research going back to the early 1990s. This is a dryland, postcolonial context that covers the contemporary administrative regions of Southern Kunene and Erongo. On the map, places in west Namibia that feature in our research include – from north to south – Sesfontein, Palmwag, Brandberg, Uis, Okombahe and Gobabeb.

Although much of this west Namibian landscape is frequently imagined and marketed today as untouched or unspoilt, and thus as pristine wilderness, it has long been inhabited by diverse African cultures who have also been entangled with wide-ranging networks of trade and exchange. For more than two hundred years west Namibia has been entwined with specifically European and North American commodity markets and strategies of resource extraction – involving the products of living entities such as whales, elephants, rhinos, and ostriches, as well as inorganic resources such as diamonds, copper and guano.[1] In other words, the context of our research has long-been a globalised African landscape: connected with and shaped by desires from afar, which have left their marks on places and peoples through colonialism and now through the application of a strongly neoliberal (i.e. market-oriented) developmental pathway.

An apocalyptic moment

Since gaining independence in 1990, Namibia has seen some new versions and intensifications of earlier market realities, now noticeably inflected by the imperative to be ‘green’. This imperative is linked with apocalyptic frames. As philosopher Slavoj Žižek has affirmed, ‘we live in apocalyptic times’[2], as the accelerating ecological alterations of the Anthropocene move us beyond known collective human experience[3].The apparent rush towards eco-catastrophe and its containment, however, is also a productive social milieu[4], populated by creative responses and diverse attempts at sustainability or ‘green’ solutions. Enduring fear that the landscape of west Namibia is on the brink of ecological collapse and catastrophe – through ‘desertification’, climate change and species extinction – creates specific apocalyptic frames that invite innovative sustainability interventions aimed at resolutions of environmental crisis.

Green performativities

These apocalyptic frames are stimulating a performative revisioning of economic activity as ‘green’, within dominant neoliberal ‘sustainable development’ formulations given new impetus as a globalising ‘Green Economy’.[5] Green economy solutions to environmental concerns embrace the modern linear, (frequently stagist),[6] developmental time of progress,[7] proposing sustainability interventions that suture economic and ecological trajectories to fit within a structuring discourse of ‘green economic growth’.

Using a combination of discourse analysis of policy texts[8] and interviews with key actors, we are exploring and theorising the constructions, rationalisations and performances of a series of market-based green performativities unfolding in the west Namibian context against an assumed universal background of homogenous, chronological time. These include: the commodification and repackaging of KhoeSan rock art heritage otherwise connected with the specific cultural ontologies of extant peoples[9]; animal trophy-hunting, or ‘killing for conservation’[10]; the commoditisation of ‘natural products’, or ‘selling nature to save it’[11]; and the proliferation of regional uranium mining activities construed as producing ‘green uranium’ as a low-carbon energy source, the direct impacts of which will be mitigated through a new conservation technology called biodiversity offsetting[12].

Ancestral times

These developmentalist green performativities jostle with a range of alternative understandings of environmental change and sustainability, held and practiced by local people with often rather different understandings of ecological and temporal dynamics, of the sources of agency, and of what practices constitute appropriate behaviours[13]. In examining these different understandings we seek to affirm that ‘difference can make a difference’[14], at the same time as recognising the attendant dangers of idealisation and romanticisation.

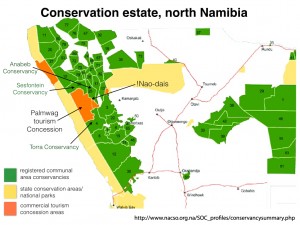

So for example, I have recently been working with older people in north-west Namibia to map places and cultural histories that have been erased from official discourses regarding land where they used to live, particularly in the Palmwag tourism concession area (see map). This area is frequently described as a ‘first class wilderness area’, but in fact was cleared of people only some decades ago.

Going into the Palmwag landscape in October and November meant observing certain protocols, in particular around a practice known as tse-khom. This involves talking in the day-time to ancestors, in this case those buried at and associated with numerous places throughout the Concession and beyond. Tse-khom introduces travellers to the ancestors – or kai khoen, i.e. ‘big or old people’ as they are known. In tse khom ancestral agencies are requested to act in the present to open the road so that travellers can see the best way to go. They are asked to mediate the activities of potentially dangerous animals such as lions, who are viewed very much as other ensouled beings who assert their own agencies and intentionality. They are asked for guidance regarding the most appropriate ways to do things, practices that have eco-ethical effects. In tse-khom, the ancestors are souls whose ontological reality means that they can assert various kinds of agency in the present, sometimes over other kinds of agency, such as that of animals.

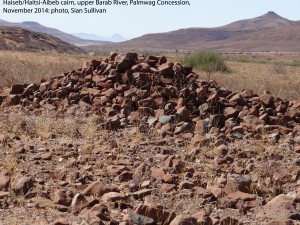

In this case, Ruben Sanib (pictured here) of a ||Khao-a Dama lineage associated with the mountainous landscapes of west Namibia, included in tse-khom acknowledgement of a key ancestor hero known in this area as Haiseb, and featuring in broader KhoeSan folklore as Haitsi-Aibeb[15]. The Haitsi-Aibeb/Haiseb cluster of stories and practices are inscribed on the landscape through large cairns found throughout the drylands of south-west Africa, from the Cape in the south to Kunene Region in the north. The image below is of a Haiseb cairn located close to a series of places in the Upper Barab River where Ruben Sanib once lived.

Haiseb/Haitsi-Aibeb cairns have featured in colonial records since the 1650s, interpreted, perhaps erroneously[16], as symbolically marking the graves of an always resurrecting Haitsi-Aibeb. As part of our intention to trace and theorise particular amodern conceptions and experiences of the west Namibia landscape we are triangulating several sources of information – colonial records, national monuments listings, databases of cairn sites, and ethnographic encounters with local people. Led by Chris Low, these data will be compiled into a region-wide Geographical Information System of Haiseb cairns and their meanings, both past and present.

Environmental change(s)

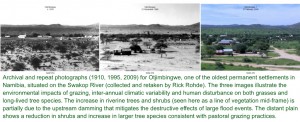

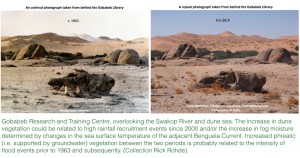

Developmentalist green economy approaches are also set within controversy regarding linear narratives and understandings of environmental change in west Namibia[17]. We seek to open up such narratives through analysing, extending and possibly exhibiting a series of repeat landscape images gathered by Rick Rohde. These bring archival images of specific scenes from the past together with repeat photographs of these same scenes in the present, thereby permitting sometimes surprising empirical (re)analyses of the materialities of environmental change at these sites[18]. The images below, for example, clearly illustrate processes of environmental change typically associated with pastoral grazing and socio-economic development in this arid savanna region.

Narratives of impending ecological catastrophe characterise environmental discourse in Namibia. Future scenarios based on general and downscaled climate models under various future scenarios[19] have predicted increasing aridity and drought, leading to degradation, loss of productivity and biodiversity declines[20]. Today, this ‘future catastrophe anxiety’ posits an expansion of desert and arid shrubs into present grassland savannas and a reduction in net primary productivity and economic potential. Understanding the extent and cause of change based on observation and empirical (rather than modelled) evidence is necessary in order to detect and accurately identify trends and threshold events. The relative impacts of land-use and climate change will also be investigated. This aspect of Future Pasts is intended as a means of comparing narratives of future change with empirical evidence and to analyse any resulting disjunction in terms of a political ecology approach.

A developing element of Future Pasts is a collaboration between Rick Rohde and Angela Impey, and a long-term monitoring programme called FogLife, established recently by Gobabeb Research and Training Centre to measure how fog-dependent species of the Namib Desert are responding to global environmental change. This collaboration, entitled FogLife and Visual/Soundscapes: Exploring the past and future ecology of the Namib through photography and acoustics, will utilise archival photographs of the FogLife study area, some of which date from 1876, comparisons with contemporary repeat photographs taken by Rick Rohde (as illustrated in the paired images below), and repeat sound recordings, made by Angela Impey, in order to document changes over time in desert ecology.

In this element of our project, then, +/- 50 repeat photos will form the basis for statistical analysis of historical vegetation change, with the results correlated with historical climatic variables to provide insights into the effects of climate change, anthropogenic impacts and ecological processes. Repeat soundscape recordings will be made annually for the next four years at selected sites within the Kuiseb, in order to gauge the effects of climate, disturbance and hydrological events on riverine biota. This draws on recent work in ‘soundscape ecology’ which emphasizes the ecological characteristics of sounds and their spatial-temporal patterns as they emerge from landscapes, focusing on the causes and consequences of, and interactions between biological (biophony), geophysical (geophony), and human-produced (anthrophony) sounds. Soundwalks with people residing close to the Kuiseb will enhance awareness and interpretation of environmental conditions and climate change[21], and responses from local residents to repeat photographs will elucidate local knowledge and the symbolic significance of the environment in daily life.

Hybrid analysis

As can be seen, we are applying a range of different methodological and disciplinary approaches to an interconnected series of environmental considerations and associated sustainabilities – hence the identification of our research as a hybrid analysis. Through this cross-disciplinary approach, we seek to fully address ‘environmental change’ and ‘sustainability’ as complex ‘wicked problems’ calling for transdisciplinary imagination[22]. Given our various disciplines, approaches and influences, a challenge is to create analytical and theoretical coherence through the juxtapositions of the different elements of our project.

One way through which we hope to pull these different empirical and theoretical threads together, is by drawing on Mike Hannis’ background in environmental ethics to flesh out what we are calling ecocultural ethics – i.e. an ethical approach that foregrounds cultural variability in ethical assumptions regarding human relationships with the nonhuman world.

Ecocultural ethics

We have coined the term ecocultural ethics because we are interested in the ethical assumptions that underlie different cultural attitudes to the nonhuman world[23]. In particular, and cognisant of producing a set of perhaps problematic dualisms, in Future Pasts we will be analysing and comparing two distinct tendencies in ecoethical framings, as represented by two different but geographically overlapping cultural contexts, or ‘ecocultures’[24].

The first is the complex of so-called ‘green economy’ policies and practices which loom large in our study area, as noted above. The second centres on indigenous, and particularly varied KhoeSan, attitudes to relationships between human and nonhuman spheres. This juxtaposition throws up several sets of theoretical questions, two of which we outline here.

First, there are questions of ethical theory, both descriptive and normative. Does the rise of calculative ‘green economy’ and ‘natural capital’ approaches to the nonhuman world mean that a utilitarian approach is becoming hegemonic in environmental decision-making? If so, why is it that calculative approaches may be considered less problematic in this context than in others (such as medical ethics)? Might it be more appropriate to link human and nonhuman flourishing by way of a eudaimonist environmental virtue ethics?[25] Are there overlaps between this kind of approach and the ways in which local stories and practices may connect the flourishing of humans and of nonhumans?

Secondly we will analyse differing concepts of sustainability and substitutability, particularly in relation to different imaginaries of what should be sustained into the future. How, for instance, might an understanding that all your ancestors are still present in the landscape affect how you interact with and value that landscape and the entities therein? To what extent might varied egalitarian principles of KhoeSan peoples reach out beyond the boundaries of the human?[26]

Future pasts

These considerations bring us back to the first term of our title, namely future pasts. Overall our project is inspired by a framing of environmental conservation – a domain of negotiated activity linked with notions of ‘sustainability’ – by philosophers Alan Holland and Kate Rawles, who articulate conservation as being ‘about negotiating the transition from past to future in such a way as to secure the transfer of maximum significance’.[27] In this definition, then, we already have an indication that:

- what is of conservation significance needs to be negotiated between different parties;

- that difference will make a difference in terms of what is considered to be significant, and how practical and policy choices are made regarding conservation;

- and, thus, that the fields of conservation and sustainability, i.e. of ‘green’ choices, will be infused with antagonism regarding whose pasts, i.e. whose values and ontologies regarding nature-beyond-the-human, become transferred forwards towards the future.

‘Sustainability’ and ‘environmental change’ are infused with productive antagonisms regarding what constitutes the past, what to value and valorise and how, and what configurations of entities and relationships beyond-the-human are deemed possible and desirable in imaginings of ‘the future’. Future Pasts encapsulates these understandings.

Click here for notes and references.

Future Pasts is funded by the AHRC for 5 years from October 2013, and conducted under a research affiliation contract with the National Museum of Namibia. We are also working with Namibian production company Mamokobo Video and Research to generate filmed material to enhance public engagement with our research.

Contact: Sian Sullivan (PI) s.sullivan@bathspa.ac.uk; futurepastscontact@gmail.com

Project website (under construction) futurepasts.net

Twitter @Future_Pasts #FuturePasts