Prof Andrew Thompson, Leadership Fellow of AHRC Care for the Future: Thinking Forward through the Past.  Cross-Posted from the Imperial & Global Forum

Cross-Posted from the Imperial & Global Forum

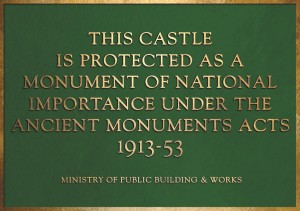

In 1913, government passed a long forgotten piece of legislation – the Ancient Monuments Consolidation and Amendment Act. The title of the act may have been commonplace but the results were certainly not, for it paved the way for the creation of the historic environment we know and enjoy today.

Fast forward a century. In 2013, government is poised to take less, not more responsibility for preserving our historic monuments and buildings. The answer to this retreat is widely felt to lie in the built heritage sector redefining its relationship with the public. But what would that entail?

Imagine a Britain without Stonehenge or Hadrian’s Wall. Imagine our historic landscape no longer embellished by great castles, cathedrals or country houses. This imagined present could easily have been a reality had it not been for the 1913 Ancient Monuments Consolidation and Amendment Act.

Imagine a Britain without Stonehenge or Hadrian’s Wall. Imagine our historic landscape no longer embellished by great castles, cathedrals or country houses. This imagined present could easily have been a reality had it not been for the 1913 Ancient Monuments Consolidation and Amendment Act.

This landmark piece of legislation paved the way for the creation of the historic environment that we know and enjoy today. Its premise was that there were monuments and buildings which belonged to our nation’s history – and that government had a duty to ensure their survival.

For the last century Britain has led the world in caring for its heritage. Yet with cuts in public spending and pressures to relax restrictions on development the future of our historic environment is looking ever more uncertain and insecure. The existing system of designation – by which buildings are listed, monuments scheduled and parks and gardens registered – is already under a lot of strain. There are many fewer local authority conservation officers today than there were a decade ago, to say nothing of the conflict of interest facing local authorities as they seek to reconcile their roles as protectors of heritage and cash-starved property developers.

In 2013, government seems poised to take less, not more responsibility for preserving our historic environment. The answer to this retreat is widely felt to lie in the built heritage sector redefining its relationship with the public.

But what would that entail?

The recession hasn’t (yet) damaged heritage sites as visitor attractions. Since 2010 numbers have actually grown. Yet the view of the past presented by many of these sites better reflects the society we were in 1913 than the one we’ve become a century later. Can history ride to heritage’s rescue?

Heritage is always playing catch up with history. It wasn’t until the 1930s that a campaign to recognise Georgian buildings swung into action. It took another twenty years for Victorian architecture to get much of a look in. And only with the upheaval in historical understanding of the 1960s – the rise of people’s, economic and social history – was the notion of heritage expanded to embrace industrial and military sites, and the heritage of the everyday as well as the exceptional.

Those who lobbied for the 1913 Act saw the country’s ancient monuments and historic buildings as encapsulating the big themes of British history. Their expectation was that by visiting these places people would be better educated about their past and better connected to their national story. This begged two questions however. What was that story? And who was qualified to tell it?

A top-down view of history, in which knowledge of the past is imparted rather than shared, seems at odds with a modern, democratic society.

Take the growth of interest in local, family and military history, or the popularity of archaeology, to say nothing of battlefield re-enactments or the more recent craze for urban exploration. If these things have anything to teach us about historical research today it is that people don’t see themselves as bystanders but as active participants. Citizen History is no less striking a phenomenon than Citizen Science.

For the built heritage sector to redefine its relationship, it must first redefine its relationship to history. Heritage is easily caricatured as ‘elite’ or ‘establishment’ history — such was the fashion on the Left in the 1980s and it lingers on today. But there is no denying that the sector has been slow – too slow – to absorb periods of major historical reassessment into its thinking about what pieces of the past we want to carry forward into the future.

This is perhaps especially true of the history of empire. For almost half a century after the Second World War, empire was effectively written out of the national narrative. The process of coming to terms with the loss of empire, and the world that was replacing it, saw the British distancing and disconnecting themselves from their empire, and, in the process, diminishing or even denying its importance. Just as the acquisition of their colonies had supposedly been little more than a matter of national pride, so too their loss would only be temporarily disconcerting.

This so-called ‘Little Englander’ view of British history proved remarkably persistent. Most general histories of Britain written in the post-war period treated the empire as if it was something that had happened overseas and was therefore external to Britain. As Salman Rushdie once remarked, ‘the problem for the English was that their history had essentially taken place overseas and so they could not understand its importance.’

All this began to change in the 1980s, a decade when empire suddenly and strikingly resurfaced in British public life. The Falklands War of 1982, as well as a spate of films and television productions which glamorized empire, while ignoring the uncomfortable realities of colonial power, helped to pave the way for a so-called ‘new’ imperial history — a wide-ranging reappraisal of the part played by empire in Britain’s past.

Yet the heritage sector has still to absorb the implications of this very different view of Britain’s history – a view in which the empire is repositioned at the heart of the national narrative.

The biggest single change to Britain over the last half century is the transformation of the ethnic complexion of its population. The racial and religious diversity which has been brought about by immigration from our colonies and former colonies has led to major differences in how we live. It isn’t at all clear that our national heritage collection has fully registered this change.

The biggest single change to Britain over the last half century is the transformation of the ethnic complexion of its population. The racial and religious diversity which has been brought about by immigration from our colonies and former colonies has led to major differences in how we live. It isn’t at all clear that our national heritage collection has fully registered this change.

The critical success of the film “12 Years a Slave” has reminded us of the importance of slavery to the prosperity of Britain’s nineteenth century elite, and prompted a re-examination of its legacy. Such a re-examination should include its legacy for our built environment. Many of the country houses considered prize pieces in the national heritage collection are expressions of the wealth and power accumulated from West Indian slave plantations. Yet you wouldn’t always know about this more sinister aspect of their past by walking around them.

The centenary of the First World War should also give us cause to pause and reflect. Just over a decade ago the first ever monument was erected to the sacrifices of the millions of still largely forgotten Indian, African and Caribbean soldiers who fought alongside Britain in the two world wars. It stands on Constitution Hill near Hyde Park Corner. Unlike the Queen Victoria Gates on the Mall, the Commonwealth Memorial Gates are not yet protected. Under current rules for listing they won’t be eligible for another twenty years. English Heritage’s criteria for protecting post-1945 structures are ‘exceptional importance’ and ‘historic interest’. Surely adequate grounds for an exception to be made.

So what should be done now?

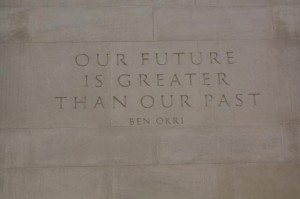

The kind of heritage protection we might collectively envisage for the future is inseparable from the question of what kinds of heritage we wish to protect. And for the public to buy into that heritage, the gap between history and heritage has to be bridged. The time is ripe for a new debate about the relationship between the two.

But this debate needs to reach out beyond the organisations that have over the last century protected Britain’s most treasured monuments and buildings to engage a much wider audience. It should address head-on the question of whose histories remain unacknowledged or under-represented in our national heritage collection.