Dr. Abbie Garrington, Lecturer in 19th & 20th Century Literature, Newcastle University

Writing a literary history of mountaineering for the modernist period, I’ve been struck by the peculiar and multifaceted relationship that both mountains and mountaineering practice have with issues of temporality. Part of the strange allure of a mountain, whether or not one is liable to climb it, is its endurance. Not only does its summit provide an expansive geographical purview, but its geology gives us a long view of a different order: one back in time. Across cultures, mountains might be venerated for their beauty, the power they confer upon those who access them, in intended abeyance of evil spirits, or for the challenge they pose for potential climbers or pilgrims. Yet veneration is also prompted by the persistence of the mountain through many human eras – it is the geological endurance of high places that lends us, as humans, our sense of relative inconsequence, impermanence and perhaps, in the case of the summit attempt, impertinence.

The lengthy timescale of a mountain’s presence on the Earth is responsible for its popularity as a figure within recent philosophical debates in the field of environmental ethics. Dr. Simon James (Durham) lately gave a talk at the Institute for Advanced Studies in the Humanities at the University of Edinburgh in which a mountain’s long life was put forward as one possible factor in the calculation of its sanctity in environmental terms. Western spiritualities do not ascribe to the mountain the status of a living being (Nan Shepherd, subject of Robert Macfarlane’s recent BBC Radio 4 documentary, notwithstanding), but we can appreciate the importance of a feature of our landscape which has maintained its place for so long a time.

Mountains can shield pockets of time, too. Representations of Tibet in early twentieth century literature, in part prompted by the expeditions of the British Everest Committee in the 1920s and ‘30s, view that mountain-ringed country as a space out of time, a kind of geographical  rendering of historical anachronism. Here, Buddhist texts protected from outside influence were said to retain a purity that had elsewhere become attenuated, linking Tibet to an ancient culture now lost. The familiar fictional construct of Tibet as ‘Shangri-La’ is dependent upon this sense that the mountains shield time, turning up in H. G. Wells’s ‘In the Country of the Blind’ (first published 1904), named in James Hilton’s Lost Horizon (1933), and also being discernible in traveller accounts of the region such as Paul Brunton’s A Hermit in the Himalayas (1937) and Fosco Maraini’s Secret Tibet (1951).

rendering of historical anachronism. Here, Buddhist texts protected from outside influence were said to retain a purity that had elsewhere become attenuated, linking Tibet to an ancient culture now lost. The familiar fictional construct of Tibet as ‘Shangri-La’ is dependent upon this sense that the mountains shield time, turning up in H. G. Wells’s ‘In the Country of the Blind’ (first published 1904), named in James Hilton’s Lost Horizon (1933), and also being discernible in traveller accounts of the region such as Paul Brunton’s A Hermit in the Himalayas (1937) and Fosco Maraini’s Secret Tibet (1951).

For Virginia Woolf – not a participant mountaineer but, as daughter of veteran Alpinist Sir Leslie Stephen, of climber stock – the mountain’s operation in a literary context is manifold, but its meanings include the persistence of the past in our present moment. Woolf was dogged by the need for a mountain story in the final years of her life, recording in her diary in June 1937: ‘I wd. like to write a dream story about the top of a mountain. Now why? About lying in the snow; about rings of colour; silence…& the solitude. I cant though. But shant I, one of these days, indulge myself in some short releases into that world?’ She overcame the feeling that she ‘cant’ speak of the summit in her short story ‘The Symbol’, written in her final months, and drawing on both the Matterhorn disaster of 1865 which had so overshadowed her father’s era, and the deaths on Everest of George Mallory and S andy Irvine in 1924 which so influenced her own. Woolf’s fictional Alpine mountain is coloured by the four deaths of the former disaster, a kind of prophecy that is fulfilled when her depicted climbers also fall. The mountain is therefore a haunted space – one which retains the ghostly presences of past climbers (or, in the case of several Himalayan peaks, the physical presence of their corpses) in a palimpsest of summit attempts.

andy Irvine in 1924 which so influenced her own. Woolf’s fictional Alpine mountain is coloured by the four deaths of the former disaster, a kind of prophecy that is fulfilled when her depicted climbers also fall. The mountain is therefore a haunted space – one which retains the ghostly presences of past climbers (or, in the case of several Himalayan peaks, the physical presence of their corpses) in a palimpsest of summit attempts.

Woolf’s mountain not only symbolises the accrual of past ascents, however, but also lifts one out of time, since the summit experience may be an ecstatic moment of pause akin to her concept of ‘moments of being’ or epiphany at ground level. Time spent ‘on the hill’ (as climbing parlance has it) is time lifted out of the rhythms of daily life, and descent can feel like a fall from temporal grace. Yet to connect with a mountain landscape is additionally to connect with the many historical epochs through which the mountain has endured. It is also to anticipate the retrospective view of future generations of climbers and mountain visitors, a sentiment perhaps best encapsulated in the unlikely realms of the Grateful Dead’s lyrics to 1969’s ‘New Speedway Boogie’: ‘I spent a little time on the mountain / Spent a little time on the hill / Things went down we don’t understand / But I think in time we will.’

Abbie’s monograph High Modernism: A Literary History of Mountaineering, 1890-1945 is forthcoming in 2016. For thoughts on mountains, literature, and mountain literature, follow her on Twitter: @abbiegarrington

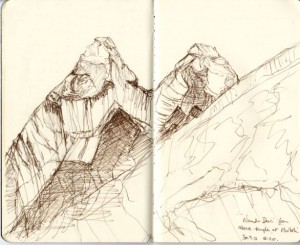

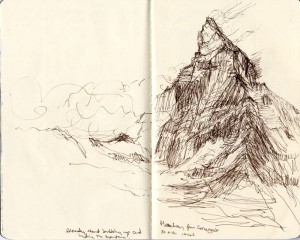

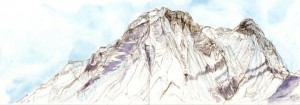

Used with permission: Images from the sketchbooks of Susan Dobson, who works in the Alps, Dolomites and Himalayas, inspired in part by modernist-period mountaineering. Find out about her work here: http://www.susandobson.co.uk

Used with permission: Images from the sketchbooks of Susan Dobson, who works in the Alps, Dolomites and Himalayas, inspired in part by modernist-period mountaineering. Find out about her work here: http://www.susandobson.co.uk