Professor Frank Trentmann, Birkbeck College,

Professor Frank Trentmann, Birkbeck College,

PI, Material Cultures of Energy: Transitions, Disruption, and Everyday Life in the 20th century. The research group consists of Frank Trentmann, Hiroki Shin, Vanessa Taylor, Heather Chappells and Rebecca Wright.

What happens when the lights go out? During a blackout it’s not only light that you lose. Electric cookers, heaters, TV and the radio stop working, and your computers, wifi and mobile phones will probably be off-line. A major part of our life today depends on the constant supply of energy. Cars might still run but traffic lights might not, nor would lifts, ticket machines, ATMs and the tube.

Such scenarios might appear the stuff of thrillers or routine in Africa and India, but even in the rich world, we have yet to overcome energy disruptions. Just to take a few examples, there were blackouts in Italy and the USA in 2003 and across Europe in 2006. Japan had rolling blackouts in 2011. It can be tempting to think energy disruptions are of recent origin, a problem that started with the oil crises of the 1970s. But this would be too simple. The 20th century is peppered with them.

Understanding the history of these disruptions better is one of the aims of the ‘Material Cultures of Energy’ research project based at Birkbeck College, University of London – the project’s other three themes look at energy futures; how rural spaces were transformed by grids; and how people managed and experienced the transition from one fuel to another. We investigate these themes by comparing the UK, Germany, Japan, North America and India, with their different energy systems, cultures and everyday practices. We are historians and a geographer, who believe a better understanding of the past can be useful for how we think and approach the future.

How did people in the past respond to energy disruption and what difference did norms and values, technologies and politics make? One thing that is clear is that energy disruption did not affect all energy users equally. In Japan in the late 1940s, families would have seen from their dark homes brightly lit factories, as the country was frantically trying to recover from the destruction of war. In the same period, British factory managers were blaming shortages on “excessive” household consumers.

Past disruptions tell us how unevenly burdens were distributed between different groups of consumers. In a very real sense, the course of disruption was often determined by society, based on ideas about who should have more energy and who less, and who should have it at what time of day or night. Culture and society shaped where and when the lights went out – not just nature or technology. It is therefore no surprise that tensions emerged not only between suppliers and consumers but also among consumers. In historical sources, we can see how different consumers were weighed against each other. After the Second World War, British homes, for example, were far more favourably treated than Japanese households, which until the 1950s were placed at the bottom of the supply list. Yet, people did not always accept their fate. In Japan, dissatisfied consumers organised protest movements. Some just ‘cheated’ suppliers.

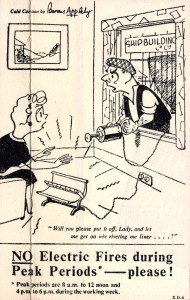

Electrical Development Association, “No Electric Fires” Campaign, c.1950. Image reproduced by permission of the Museum of Science and Industry, Manchester.

Such distributional conflicts also affected the rhythm of day and night, as governments tried to shift electricity use out of peak hours. The lack of energy triggered a reconfiguration of work and everyday life. During the 1946/7 fuel crisis in Britain, waking up late would have meant missing out on hot water and hot breakfast. Household chores needed to be done within specified hours when electricity was permitted, or they had to be done without electrical appliances at all. In East Germany, industrial workers were told to work into the night – in order to shift the peak hours. Such shift work had knock-on effects on eating rhythms, sleeping, shopping and child care that were particularly hard on mothers.

Understanding how past shortages worked themselves out provides vital knowledge in helping us to think about how societies might deal with such situations in the future. In November 2014, we met with international experts at Caltech to look at various scales of scarcity, from scenarios of population growth in the past to the challenge of renewable energy in the future. At the symposium, historians, social scientists, engineers and scientists examined various types of scarcity, including water, food and energy, and the interplay of natural, economic and political forces.

Today, there is once again talk among politicians and energy providers in Britain and Europe about future blackouts and a more precarious allocation of energy. Developing nations cannot expect smooth growth and energy security either. If there is one lesson from the past, it is that it is too simple to trust technology will fix the problem. Abundance and scarcity go hand in hand. Shortages involve politics and culture, as do societies’ strategies to deal with. What people did when the lights went out in the past could tell us something about our flexibility and resilience in the future.