Ryan W. Heyden

As historians have engaged in a widespread and heated discussion about the history of human rights and its relationship to contemporary political and social developments around the world, many have also turned to humanitarianism. With new and protracted conflicts raging in the Middle East and other parts of the world, and with the growing number of natural disasters caused by a rapidly changing climate, humanitarian workers and organizations are busier than ever before. And yet, the scholarly literature on humanitarianism and the labours of humanitarian workers since the 1700s was, until the last decade or so, focussed mainly on humanitarian aid delivered to various sites of conflict after the end of the Cold War. Political scientists were the primary researchers pushing this field of humanitarian studies. Thankfully, historians have joined this scholarly discussion, adding a much-needed historical perspective. Historians at all levels are trying to understand the origins and development of humanitarianism, asking many vital questions: what has mobilized empathy for those suffering during war; how has humanitarianism been used and abused by the West in its effort to colonize the Global South; how can we understand the often-fraught gender and power dynamics involved in humanitarian campaigns and in the administration of aid; and, what is the relationship between humanitarianism and human rights? Scholars are also historicizing humanitarian institutions – like the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), Oxfam, Médecins Sans Frontières, CARE, and older institutions that tried foster “humanitarian sensibilities” like religious groups (missionaries) and the abolitionist movement – and asking how they fit into this budding historical narrative?

Thankfully, historians have joined this scholarly discussion, adding a much-needed historical perspective. Historians at all levels are trying to understand the origins and development of humanitarianism, asking many vital questions: what has mobilized empathy for those suffering during war; how has humanitarianism been used and abused by the West in its effort to colonize the Global South; how can we understand the often-fraught gender and power dynamics involved in humanitarian campaigns and in the administration of aid; and, what is the relationship between humanitarianism and human rights? Scholars are also historicizing humanitarian institutions – like the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), Oxfam, Médecins Sans Frontières, CARE, and older institutions that tried foster “humanitarian sensibilities” like religious groups (missionaries) and the abolitionist movement – and asking how they fit into this budding historical narrative?

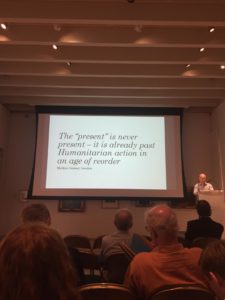

This rather brief outline of the field and its vital questions are merely a sampling of the work being done by historians around the world. It is also a snap shot of some of the themes I took away from this year’s iteration of the Global Humanitarianism Research Academy. In July 2018, I had the privilege of travelling to the University of Exeter in the UK and the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) Public Archive and Library in Geneva, Switzerland with the generous support of Care for the Future, the Leibniz Institute for European History, the German Historical Institute in London, and the ICRC. During my two-week intensive  workshop and archival work, I had the pleasure of meeting and exchanging views with established scholars, newly-minted PhDs, and fellow PhD Candidates. I learned a lot during what can only be called a two-week academic adventure! While I could probably write ad nauseum about what I learned, my archival finds, and the people I met, I want to draw attention to a few lessons.

workshop and archival work, I had the pleasure of meeting and exchanging views with established scholars, newly-minted PhDs, and fellow PhD Candidates. I learned a lot during what can only be called a two-week academic adventure! While I could probably write ad nauseum about what I learned, my archival finds, and the people I met, I want to draw attention to a few lessons.

The first lesson is what I learned from talking to current humanitarian practitioners. We were fortunate enough to listen to and talk with two humanitarian practitioners active in the ICRC, Markus Geisser, Senior Humanitarian Affairs and Policy Advisor, and Yves Daccord, Director General. In both cases, I was reminded of the continuing importance of historical research to the ongoing functions of the Red Cross movement and humanitarianism more broadly. M. Geisser offered a first-hand account on the changing nature of humanitarian action from the twentieth to the twenty-first century. Having worked in the field for many years, Geisser witnessed and helped to create many of the security measures that ensure the safety of humanitarian workers in conflict zones. He also talked of how the priorities of security and achieving what one sets out to do when entering a conflict zone to administer aid are balanced both in central operations in Geneva and on the ground. As a researcher sitting in an archive, it is easy to be critical of the various decisions and ideological motivations of our historical subjects, but from listening to Geisser’s talk, I can see also how humanitarian workers are trying to draw on the lessons of the past, maintain a consistency in their missions, and ultimately how changing geopolitics has transformed the substance of humanitarian work – a point well-articulated in Geisser’s discussion of the current use of drones to deliver aid and monitor humanitarian crises.

I had a similar reflection listening and speaking with the ICRC’s Director General. Director General Daccord spoke with us on a number of issues, from the role of the ICRC in protracted conflicts and the renewed criticisms of humanitarian organizations in the media around the #MeToo movement, to his work as a journalist before starting with the Committee, the relationship between humanitarian organizations, and the benefits of the ICRC as a long-time Swiss-led organization. In each case, I was reminded that humanitarian action and work are inherently political tasks that require excellent media communication as much as they need a strong bureaucracy. But, it was the importance of research and reflection that stayed with me as I listened to the Director General, a point well stressed throughout the discussion. Indeed, two other Committee employees took the time to speak with us, Cedric Cotter and Jean-Marie Henckaerts. Both researchers, Dr. Cotter and Dr. Henckaerts discussed the role that researchers play in the present operations of a humanitarian organization. With Dr. Henckaerts’ work updating the commentaries of the Geneva Conventions and Dr. Cotter’s policy work and research on how humanitarian law is understood and practiced in current conflicts in which the ICRC is present, one can see that researchers are crucial to the ongoing actions, development, and critical self-reflection that Michael Barnett argued all humanitarian organizations must go through from time to time.

While I was reminded of the contemporaneous importance of historical research on the practice of humanitarianism and vice versa, I also I learned a lot from my peers. I remain deeply impressed by the work of those I met during my time at the Academy. I think a few thoughts on how their work and our discussions have changed (and reinforced) my outlook on the history of humanitarianism are warranted. My fellow GHRA  participants are tackling questions small and large in their research in the hope that they too can help answer many of these unanswered questions in the history of humanitarianism. With Elena Kempf’s work on international humanitarian law and weapons prohibition during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, I learned that it is important to ask why people have cared about the prohibition of one type of weapon and not the other in the name of “humanity,” while also looking at how those same laws and weapons helped to reinforce attitudes of race, colonialism, and empire. Dr. Elisabeth Piller’s work on “Aid for Belgium,” a massive American-led relief campaign during the Great War, reveals a similar prerogative of historically why but also how masses of people can be mobilized to help others and across national boundaries. In this case, “Aid for Belgium” during WWI executed a massive marketing campaign that stretched from the United States to New Zealand. The politics of humanitarianism and the marketing of humanitarian campaigns were as vital to humanitarian action in the past as they are in the present. Dr. Monique Beerli’s discussion of internal political struggles in the post-1945 ICRC showed also that internal politics was (and is) as equally important to the success of humanitarian action and planning as the external politics that Elena and Elisabeth clearly indicate.

participants are tackling questions small and large in their research in the hope that they too can help answer many of these unanswered questions in the history of humanitarianism. With Elena Kempf’s work on international humanitarian law and weapons prohibition during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, I learned that it is important to ask why people have cared about the prohibition of one type of weapon and not the other in the name of “humanity,” while also looking at how those same laws and weapons helped to reinforce attitudes of race, colonialism, and empire. Dr. Elisabeth Piller’s work on “Aid for Belgium,” a massive American-led relief campaign during the Great War, reveals a similar prerogative of historically why but also how masses of people can be mobilized to help others and across national boundaries. In this case, “Aid for Belgium” during WWI executed a massive marketing campaign that stretched from the United States to New Zealand. The politics of humanitarianism and the marketing of humanitarian campaigns were as vital to humanitarian action in the past as they are in the present. Dr. Monique Beerli’s discussion of internal political struggles in the post-1945 ICRC showed also that internal politics was (and is) as equally important to the success of humanitarian action and planning as the external politics that Elena and Elisabeth clearly indicate.

I also learned from those trying to historicize some of the most important issues the world is facing today. For example, the maintenance and function of a refugee regime were recurring topics of discussion at the GHRA this year, with Jacob Schönhagen and Rebecca Viney-Wood both working on these issues. Jacob’s analysis of the emergence of a refugee regime not in the 1940s, but actually much later in the 1960s, challenges my perception of how post-war Europe dealt with the mass movement of people after 1945. With historians like G. Daniel Cohen arguing that the immediate post-war migration crisis was crucial for the emergence of modern human rights discourses, Jacob offers an important counter point that in fact the issue of security in the aftermath of Germany and Japan’s defeat and the worsening relationship between the Soviet Union and the United States – not a desire to establish legal and inalienable rights – created the foundation of the modern refugee regime. Rebecca’s work on the Nansen Passports, in turn, is vital for how we understand how people cross borders and what it meant (and means) to be stateless. Her work,  zeroing in on refugee stories and experiences using the Nansen passport system, is revealing of how humanitarianism and humanitarian action like facilitating safe migration, something that defies national borders at its core, is still very much bounded by an international order built around the nation state.

zeroing in on refugee stories and experiences using the Nansen passport system, is revealing of how humanitarianism and humanitarian action like facilitating safe migration, something that defies national borders at its core, is still very much bounded by an international order built around the nation state.

My fellow participants additionally reminded me of the important relationship between the history of humanitarianism and the history of human rights. Dr. Emma Mackinnon’s work on the development of human rights discourses in the 1960s in the United States and France (and its colonies) and those discourses connections to important documents like the Declaration of Independence is an excellent case in point of how the language used to promote humanitarian action was (and still is) tied up in the discussions of people’s inviolable rights. Christoph Plath’s work on the emergence of “collective rights” in the 1970s and 1980s, shows the importance of changing international relationships, economic structures, and the role of international institutions in the discussion of human rights discourses. Humanitarian action and humanitarianism are an important part of the discussion of the so-called right to development that dominated discussions about human rights and collective rights in the final two decades of the Cold War.

And last, I left reflecting on the importance of power (that is, the unequal power relationships between benefactor, donor, and subject) in the history of humanitarianism. Jennifer Carr’s work on protracted refugee camps in Jordan and Sahrawi in the 1970s is indicative of this history. As Jennifer explained, humanitarians in their efforts to provide professional medical aid to those in need also acted as the arbiters of “value”; humanitarians make decisions about who (and how) to treat someone and with what materials. These decisions are often done not in collaboration with the subjects of humanitarianism but instead for them – a reality that creates deep imbalances between those seeking to provide and administer aid and those in need of it. Megan Riley’s work on refugee, and later concentration, camps in southern France during the interwar period and WWII under the Vichy Regime reveals a similar imbalance in power relationships. In this case, it is not necessarily the relationship between humanitarian subject and actor, but rather between state and donor as the American Red Cross decided to remain silent on clear violations of human dignity in a French-based concentration camp in order to maintain its access to those in need. Finally, Margot Tudor’s work on UN Peacekeeping missions in the decolonized world interrogates the persistent imbalance of power between the West and the Global South. As Margot described to us, the arrival of peacekeeping forces in the Congo in 1961 also meant tidings of western paternalism as peacekeepers “helped” the struggling Congolese state to reimpose law and order and create a bureaucratic state that reflected and would easily fit into the Western international order.

And last, I left reflecting on the importance of power (that is, the unequal power relationships between benefactor, donor, and subject) in the history of humanitarianism. Jennifer Carr’s work on protracted refugee camps in Jordan and Sahrawi in the 1970s is indicative of this history. As Jennifer explained, humanitarians in their efforts to provide professional medical aid to those in need also acted as the arbiters of “value”; humanitarians make decisions about who (and how) to treat someone and with what materials. These decisions are often done not in collaboration with the subjects of humanitarianism but instead for them – a reality that creates deep imbalances between those seeking to provide and administer aid and those in need of it. Megan Riley’s work on refugee, and later concentration, camps in southern France during the interwar period and WWII under the Vichy Regime reveals a similar imbalance in power relationships. In this case, it is not necessarily the relationship between humanitarian subject and actor, but rather between state and donor as the American Red Cross decided to remain silent on clear violations of human dignity in a French-based concentration camp in order to maintain its access to those in need. Finally, Margot Tudor’s work on UN Peacekeeping missions in the decolonized world interrogates the persistent imbalance of power between the West and the Global South. As Margot described to us, the arrival of peacekeeping forces in the Congo in 1961 also meant tidings of western paternalism as peacekeepers “helped” the struggling Congolese state to reimpose law and order and create a bureaucratic state that reflected and would easily fit into the Western international order.

What stands above is merely a glimpse of the fascinating work my colleagues are doing and each of them have influenced how I understand  the terms humanitarianism, human rights, and most broadly, humanity. I return to my doctoral research on the German Red Cross in post-1945 divided Germany with fresh eyes and prepared to interrogate the role of international institutions, emerging discourses on human rights, the emergence and ultimate failures of the international refugee regime, and the continued imbalance between the West (itself waging a Cold War) and the Global South (undergoing massive political, economic, and social changes with the onset and progression of decolonization). In the twentieth century, Germany – twice the defeated stated – was both the subject of humanitarian aid and a humanitarian actor around the world. Germany’s place in this wider history of humanitarianism, as benefactor and subject, remains understudied.

the terms humanitarianism, human rights, and most broadly, humanity. I return to my doctoral research on the German Red Cross in post-1945 divided Germany with fresh eyes and prepared to interrogate the role of international institutions, emerging discourses on human rights, the emergence and ultimate failures of the international refugee regime, and the continued imbalance between the West (itself waging a Cold War) and the Global South (undergoing massive political, economic, and social changes with the onset and progression of decolonization). In the twentieth century, Germany – twice the defeated stated – was both the subject of humanitarian aid and a humanitarian actor around the world. Germany’s place in this wider history of humanitarianism, as benefactor and subject, remains understudied.

It is safe to say that I walked away from the Global Humanitarianism Research Academy with an appreciation for the current work being done and struggles faced by the ICRC and the Red Cross. I also walk away with a renewed curiosity in this burgeoning field. My fellow participants shared their projects and insights and generously offered their constructive criticisms of my work. The academy leaders, Professor Andrew Thompson, Prof. Dr. Johannes Paulmann, Dr. Fabian Klose, Dr. Stacey Hynd, Dr. Marc-William Palen, Professor Irène Herrmann and Guy Thomas of the ICRC all asked us to question our assumptions, encouraged our bold research questions, and offered valuable advice about sources along the way. And, of course, Dr. Susan Leedham patiently organized the events, and fielded our many questions in the lead-up to and throughout the two weeks. To them, and to the many new colleagues and friends I made during my time at the GHRA, I am forever grateful.

the two weeks. To them, and to the many new colleagues and friends I made during my time at the GHRA, I am forever grateful.